10 January 2026

Whether it’s military reconnaissance or wedding photography, using quadrotors (also known as multirotors) has become the standard. However, one of the primary limitations of today’s electric motor multirotors is their limited endurance, which is primarily due to battery capacity.

Using internal combustion (IC) engines would be much more efficient. While gasoline offers more than 25 times the energy density of lithium-polymer batteries, IC engines respond sluggishly compared to electric motors. Anyone who has driven a car with an IC engine knows the lag between pressing the accelerator and feeling the engine respond—a delay that would be catastrophic for a quadrotor trying to maintain stable flight.

Quadrotors are inherently unstable flying machines. They stay airborne and level only because their electric motors can change speed in milliseconds, constantly adjusting thrust to maintain balance. Owing to delays in carburetors, fuel-air mixing, and combustion cycles, an IC engine seems fundamentally incompatible with the rapid response required to stabilize an IC engine-powered quadrotor.

IC engine-based bi-rotor on a test stand

IC engine-based bi-rotor on a test stand

Equipping IC engines for quadrotor control is akin to transforming a marathon runner into a 100-meter sprint champion. That’s the engineering challenge Ajith, a PhD student whom I am co-guiding with Prof. Ramakrishna, tackled in his research, the results of which are published in an article titled “Throttle-controlled internal combustion engines as propulsion and control units for high endurance quadrotors: a feasibility study,” recently published in Aerospace Science and Technology.

Electric quadrotors face a fundamental limitation: endurance—the duration they can remain airborne. For a typical 14 kg quadrotor powered by LiPo batteries, flight endurance is around 40 minutes. This severely restricts applications that require extended flight times, such as agricultural monitoring, pipeline inspection, search and rescue, and long-range surveillance.

IC engines offer a compelling alternative. A preliminary comparative study we conducted shows that replacing electric motors with IC engines in the same 14 kg quadrotor—while maintaining the same payload capacity—extends endurance to approximately 86 minutes, more than doubling the flight time. Apart from gasoline’s superior energy density, the decreasing fuel weight as it gets consumed reduces the thrust required for hovering, further reducing fuel consumption.

The challenge isn’t simply mounting an IC engine where an electric motor used to be. Three fundamental problems emerge:

Slow response: Open-loop testing of our candidate engine (a 35cc two-stroke model aircraft engine) revealed rise times exceeding 2 seconds for a 300 rpm speed change. Electric motors achieve the same change in tens of milliseconds—two orders of magnitude faster.

Speed instability: The engine exhibited rpm fluctuations of up to ±500 rpm at certain operating speeds, even with a constant throttle position. Whereas, with electronic speed controllers in place, electric motors precisely maintain the commanded rpm.

Unpredictable behavior: For example, the engine would spontaneously depart from idle speed after ignition, settling at a random speed between 2,200 and 4,200 rpm, making reliable operation difficult.

This is in addition to other technical problems—for instance, IC engines typically used in small aerial vehicles are designed to operate with their rotational axis pointing horizontally most of the time, whereas a quadrotor requires the engines to be mounted vertically resulting in fuel flow problems.

Thrust measurements made after attaching a 20-inch propeller revealed that a 14 kg quadrotor requires each engine to operate between 4500-6300 rpm, producing 35-70 N of thrust per rotor. Within this regime, uncontrolled engines showed standard deviations of 50-200 rpm—variations that would make stable flight impossible.

The way forward was to improve engine response. Rooted in feedback control theory, Ajith designed a controller using measured engine speed in a feedback loop to enhance the engine’s speed response. He developed a control architecture combining feedforward and feedback paths to dramatically improve engine response:

Feedforward component: Rather than relying purely on feedback correction, the controller uses a pre-mapped relationship between throttle position and engine speed (obtained through systematic characterization experiments). Given a desired rpm command, this provides the nominal throttle setting that brings the engine close to the target speed. This approach overcomes the sluggish response that would result from feedback-only control of the highly nonlinear throttle-to-rpm relationship.

Gain-scheduled PID feedback: As the feedback controller, we have the standard PID (proportional-integral-derivative) controller. The core innovation lies in making the PID controller adaptive. Unlike conventional PID controllers with fixed gains, our design varies the proportional (Kp) and integral (Ki) gains as functions of the reference speed. This adaptation is necessary because engine dynamics change dramatically across the operating range—gain values that work at 4500 rpm do not give good results at 6000 rpm.

The gain scheduling functions were derived systematically: we manually tuned Kp and Ki values at discrete reference speeds (4,500, 5,000, 5,500, 5,800 rpm), then fitted third-order polynomials through these points. In this work, we maintained a constant derivative gain, Kd, for all speeds.

We implemented the developed controller on a custom circuit board designed around an Arduino Mega microcontroller, operating at a frequency of 40 Hz. The results were promising:

Reduced variation: The controlled engine maintained speeds within ±100 rpm across the entire operating range—a five-fold improvement over uncontrolled operation.

Faster response: The rise time for a 300 rpm step change dropped from 2,085 milliseconds (open-loop) to just 104 milliseconds (controlled)—a 20x improvement that brings IC engine response into a regime suitable for quadrotor attitude control.

Consistent performance: Engine speeds measured during testing showed that 89% of data points remained within ±50 rpm of the reference speed, and 97% stayed within ±80 rpm.

Robustness: With only the feedforward throttle map updated, the same controller architecture worked successfully on two additional engines of the same model without retuning the PID gains—demonstrating both robustness and practical deployability.

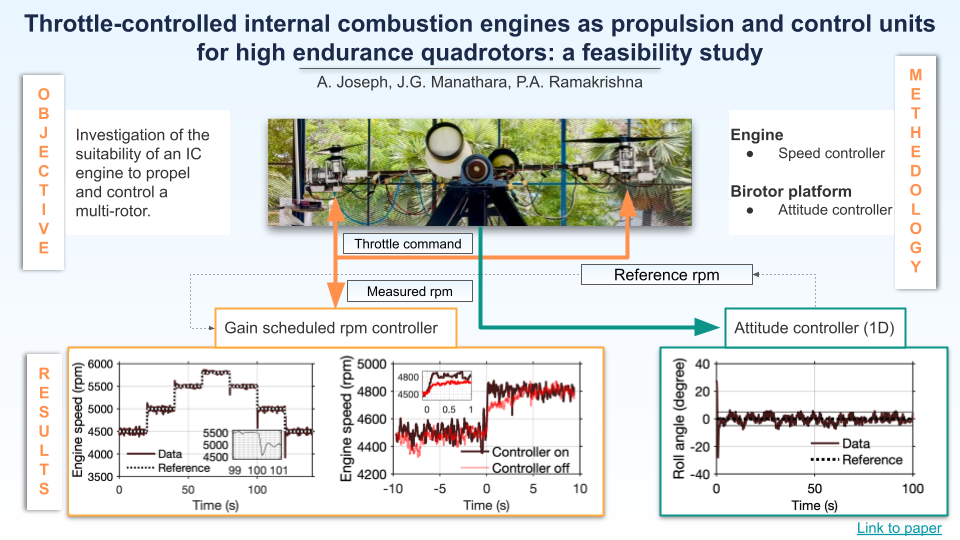

Speed and thrust measurements via benchtop tests are one thing; actual attitude control is another. To demonstrate the feasibility of attitude stabilization, we built a seesaw-like bi-rotor test stand—essentially half a quadcopter (see the figure at the beginning of the post). Two IC engines with propellers were mounted at opposite ends of a bar free to rotate about a central pivot. The objective: use differential thrust from the IC engines to maintain a level attitude.

We designed a cascaded controller architecture: an outer attitude controller (combining PID control on angle error and PD control on angular rate error) commands differential rpm changes, which inner speed controllers (the gain-scheduled PID developed earlier) deliver by adjusting individual engine throttles.

The system successfully stabilized the seesaw at the commanded zero-degree position for over 200 continuous seconds—the duration of the experiment. The angular position was maintained with a mean of 1.38 degrees and a standard deviation of 3.94 degrees—79% of the time the bi-rotor stayed within ±5 degrees, and 95% of the time within ±8 degrees. Thus, we demonstrated that IC engines, when augmented with a speed controller, can indeed be used to construct quadrotors—using them as propulsion and control units.

The full technical details, including the complete control system design, experimental methodology, and quantitative results, are available in our published paper.

Here is a graphical abstract of our work:

The research revealed important practical challenges. Hobby-class IC engines are designed for fixed-wing aircraft with horizontal shaft orientation. Mounting them vertically for multirotor applications creates fuel delivery issues and requires significant carburetor adjustment—typically opening the low-speed and high-speed needles 15-20% beyond standard settings to prevent stalling. Further, tuning the engine via its low-speed and high-speed needles for proper operation is more of an art than a science!

While our engine speed feedback controller greatly improved the engine response, some limitations still need to be addressed. When the desired engine speeds are suddenly changed (step input), the engine response results in overshoots. Our controller exhibited significantly larger overshoots during speed step-downs compared to step-ups. Further, occasional transient disturbances caused the engine to deviate from the reference rpm. These suggest opportunities and the need for further refinement through better control strategies or hardware modifications.

This work demonstrates that the fundamental barrier to IC engine-powered multirotors—slow response—can be overcome through the design of an appropriate control system. By addressing the IC engine speed control problem, we’ve shown that:

The path is now open to building full IC engine-powered quadrotors with high endurance. Our next step is to construct and flight-test a complete four-engine quadrotor prototype.

Beyond the immediate application, this research illustrates a broader principle: solutions to certain problems (such as the endurance of quadrotors) need not wait for path-breaking advancements in battery technology, but rather can be achieved through existing technology by compensating for its inherent limitations. Gasoline’s energy density advantage has been known for decades; what was missing was the ability to make IC engines behave fast enough for inherently unstable platforms. That’s what this work provides.